Article

Article

As COVID-19 continues to spread, hospitals in the hardest-hit areas operate at near capacity. Professor Elliott N. Weiss believes that understanding capacity management and other fundamental concepts in operations can help us make sense of the current crisis and invites us to examine it through the lens of operations.

As COVID-19 continues to spread, hospitals in the hardest-hit areas operate at near capacity. Professor Elliott N. Weiss believes that understanding capacity management and other fundamental concepts in operations can help us make sense of the current crisis and invites us to examine it through the lens of operations.

Insights from

Written by

The United States hit another grim milestone in the war on COVID-19. Confirmed cases approach 4 million.1 A devastating new wave of infections across the South and large parts of the West threatens to overwhelm the health care system. In the hardest-hit areas, intensive care units (ICUs) operate at capacity, and hospitals scramble to meet soaring demand.

Some states that had eased lockdowns were forced to roll back their reopening efforts and reimpose restrictions to stem the surge in coronavirus cases.

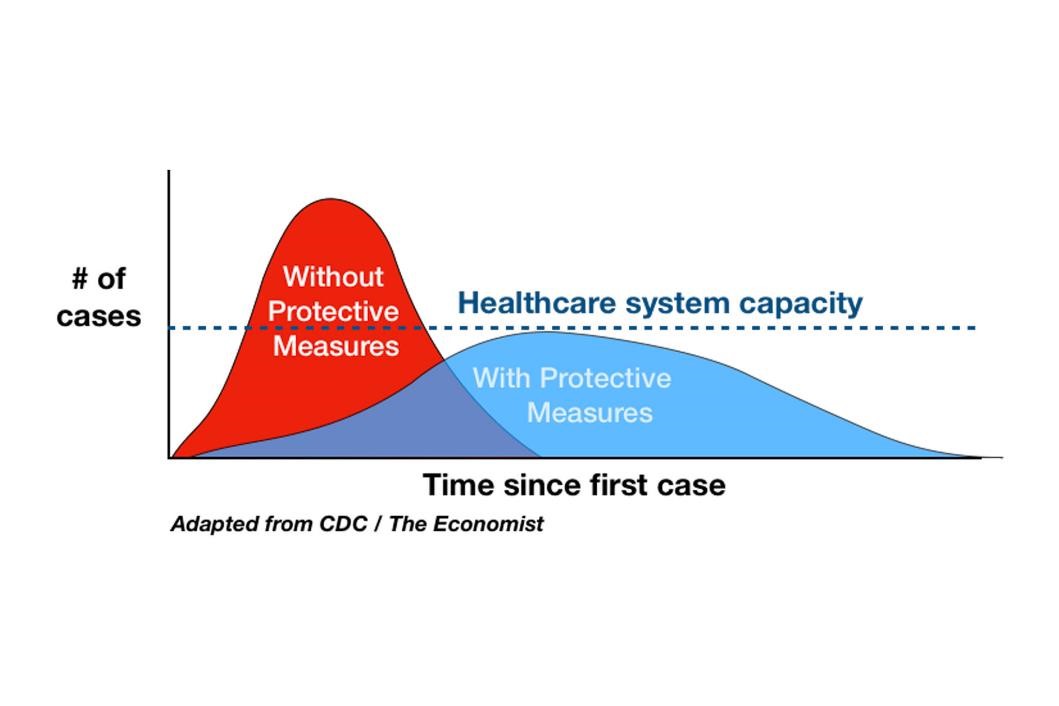

“When a black swan event like this pandemic happens,” said Darden Professor Elliott N. Weiss, an authority on operations management, “demand for ICU rooms is so high, and the facility capacity is so limited, that we’re in trouble. So the idea is that those protective measures like social distancing and wearing masks will help us control the demand so that it doesn’t exceed the capacity.”

According to Weiss, understanding capacity management and other fundamental concepts in operations, such as supply chains and lean thinking, can help us make sense of the current crisis. Weiss recently led a webinar, Everything I Know About Operations I Can Use to Explain the COVID-19 Crisis, to examine the pandemic through the lens of operations. What follows are the highlights from the webinar.

Hospital capacity, said Weiss, is the number of patients who can be seen and treated. “It’s equal to the available time that we have to see patients, divided by the time per patient. So if you had 10 beds and a person took one bed per day, you could see 10 patients.”

There are three levers that allow us to control capacity and avoid hospital or ICU overcrowding and long waits: 1) Fewer patients, 2) More available time and 3) Less time per patient.

The new COVID-19 epicenters in the Sunbelt states are facing the kind of dramatic spikes in infections that quickly overwhelm a health care system. And that’s exactly what we don’t want, said Weiss. We want fewer patients, hence the protective measures, like lockdowns. Those measures, combined with testing and the trace-and-isolate strategies, can help flatten the curve, as illustrated below.

Another way to control capacity is by opening additional facilities and by finding “hidden time.” The latter can be achieved by identifying and eliminating bottlenecks, said Weiss. For example, to relieve bottlenecks in testing, several labs are working on new testing methods that eliminated a time-consuming step of RNA extraction.2

Hospital capacity can be also increased by spending less time per patient. “The question is,” said Weiss, “can I get the patients through more quickly without affecting the quality of care?” Remdesivir, a drug for COVID-19 patients recently approved for emergency use, is a case in point. According to a recent study, remdesivir can cut down recovery time by 31 percent.

Years ago, experts predicted that just-in-time inventories, which the health care industry embraced in the name of cost-cutting and efficiency, would make us vulnerable in a pandemic.3 Unsurprisingly, when the first wave of infections hammered the Northeast, hospitals didn’t have enough space, ventilators and personal protective equipment (PPE) to handle an influx of critically ill patients.

“The reason we’re in this situation now,” said Weiss, “is the idea that inventory is considered a waste; it’s taking up space and tying up money and resources. So the question is: Is it possible to be prepared for a disruptive event like the pandemic?”

No individual hospital could tackle this problem on its own, according to Weiss. The solution involves working with the government. “Now we have a policy question, how do we handle this?” said Weiss. “Should we have had inventory, a strategic stockpile, like we have for oil and gas? Should we have had extra capacity ready to produce equipment as needed?”

The problem is, it’s hard to predict demand. When the COVID-19 crisis exploded, “demand for PPEs went all the way up,” said Weiss. “I can’t think of anything more variable than that.”

According to Weiss, there are three ways to manage variability: inventory, capacity or lead time, as illustrated below.

“I either have stuff sitting around, just in case,” said Weiss, “or I have capacity, which means I can make it just in time. Or, I have lead time, but during the pandemic, waiting is not an option. So I either need lots of inventory, or I need lots of capacity, or I’m stuck where I am right now.”

So why can’t we quickly make PPEs and other critical equipment? “We have this supply chain with all those interdependencies,” said Weiss. “It’s spread out all over the world, and it’s going to take us a long time.”

At the heart of most supply chains is China. It manufactures components for many goods, including pharmaceuticals, PPEs and medical equipment. The outbreak in China created a supply disruption, for which most U.S. companies were unprepared.

The pandemic has exposed how vulnerable global supply chains are to disruption. The solution? “One of the things you have to do,” said Weiss, “is diversify the risk of your supply chain.”

Another useful concept from operations is lean thinking — the philosophy of maximizing customer value while minimizing waste — introduced decades ago through the famed Toyota Production System.

Weiss defines lean as “the relentless pursuit of creating value through the strategic elimination of waste.” Waste manifests itself as non-value-added activities, unevenness and overburden. “The idea is,” said Weiss, “that we’re going to create value for customers and we’re going to try to eliminate the waste. So in the COVID-19 crisis, where do I see waste in hospitals?”

There’s clearly overburden in the system. “We have this valuable resource, this bottleneck, the hospital,” said Weiss, “and we’ve diverted people away from it through things like telemedicine, and that’s a great example of creating extra capacity. We don’t want people with skin rashes coming to the ER, which needs to be used for the most serious cases.”

The second surge of COVID-19 infections is poised to overwhelm hospitals in the Sunbelt states, some of which are reporting the highest-ever number of beds and ventilators used for COVID-19 patients.

How will we solve those problems?

“We have all of these mathematical models,” said Weiss, “but what it comes down to is the people.” Lean, according to Weiss, continuously strives to improve safety, quality, flexibility and productivity by involving all employees in problem-solving. “Everyone,” said Weiss, “is empowered to identify problems and fix them as they occur.”

Take doctors in a New York hospital, who kept patients alive during the first wave of COVID-19 through sheer ingenuity. Faced with the shortage of life-saving ventilators, they jury-rigged them so that one device could be shared by two patients.4

The U.S. health care workers fighting on the pandemic’s frontlines are doing the best they can with what they have. However, as cases surge, how far will they be able to stretch their creativity?

This article was developed with the support of Darden’s Batten Institute, at which Gosia Glinska is associate director of research impact.

Weiss is a top authority in many aspects of manufacturing, including inventory control, manufacturing planning and scheduling, manufacturing project management, materials management, service industry operations, total productive maintenance and lean systems.

Weiss is the author of numerous articles in the areas of production management and operations research and has extensive consulting experience for both manufacturing and service companies in the areas of production scheduling, workflow management, logistics, lean conversions and total productive maintenance.

B.S., B.A., MBA, Ph.D., University of Pennsylvania

What Can Operations Management Teach Us About the COVID-19 Crisis?