Article

Article

Legislation on “opportunity zones” is intended to encourage investment in economically distressed communities by providing significant tax incentives to investors. Professor Mary Margaret Frank and alumnus Ben Cullop (MBA ’11) explain how this new program works and what its repercussions may be.

Legislation on “opportunity zones” is intended to encourage investment in economically distressed communities by providing significant tax incentives to investors. Professor Mary Margaret Frank and alumnus Ben Cullop (MBA ’11) explain how this new program works and what its repercussions may be.

Insights from

Buried in the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act is a provision based on a rare bipartisan legislative proposal sponsored by Senators Cory Booker (D–N.J.) and Tim Scott (R-S.C.) and Representatives Pat Tiberi (R-O.H.) and Ron Kind (D-W.I.). The intent of the provision is to incentivize investment in economically distressed communities that are experiencing persistent poverty and a slower recovery after the financial crisis of 2008. Taxpayers are able to reduce their capital gains taxes owed on the sale of appreciated investments if they reinvest the gain in qualified funds that invest in designated distressed areas, called “opportunity zones,” within 180 days of realizing the capital gain.

Governors of each state nominated census tracts in low-income communities (LIC) that met the requirements laid out in the law — elevated poverty rates, lower than average median income, etc. The broad criteria led 57 percent of all census tracts to qualify (the fact that 57 percent of U.S. census tracts meet some criteria for poverty is a topic for a different day). Governors controlled the process and could nominate 25 percent of their LIC tracts for certification by the U.S. Treasury Department.

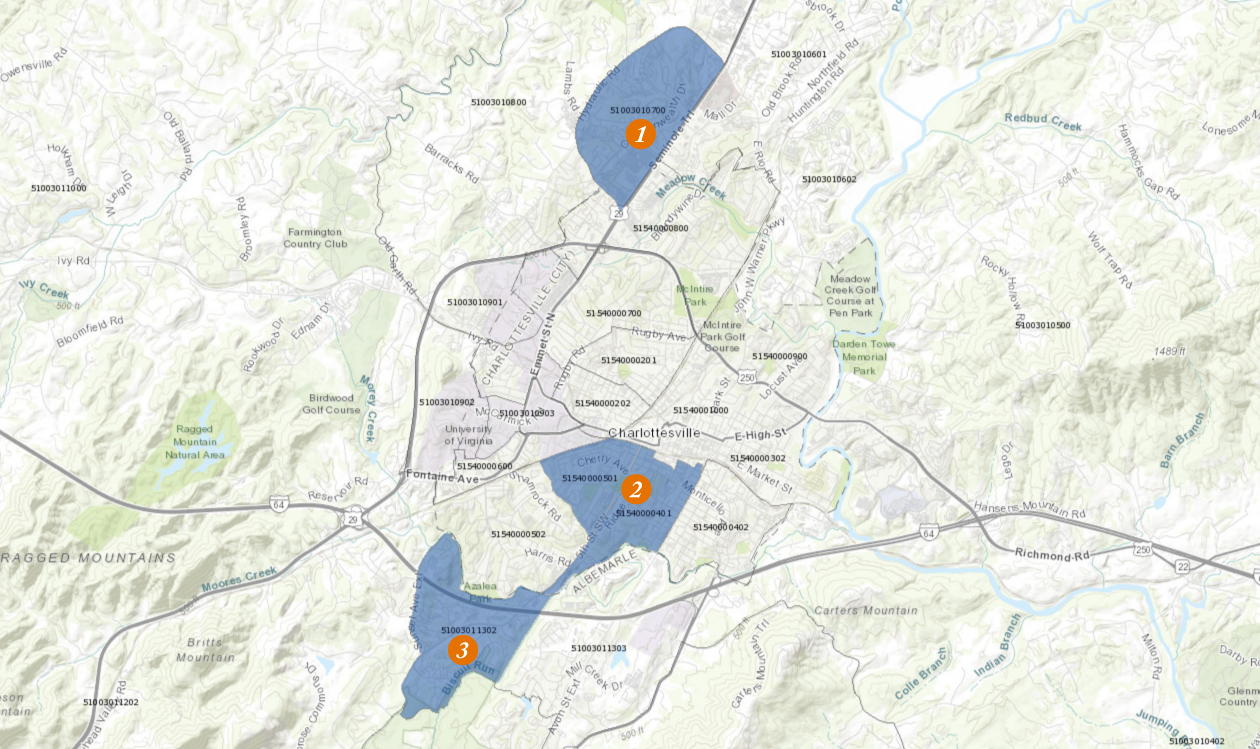

Each state and territory nominated the maximum allowed LIC tracts, and the U.S. Treasury Department certified the 8,764 areas in the summer of 2018. With 879, California has the most opportunity zones; Texas has 628, and Virginia is 11th with 212. Nine states had 25 zones. Charlottesville and Albemarle County each contain two zones, as shown below.

Taxpayers must invest through an opportunity zone fund, an investment vehicle that self-designates by filing IRS Form 8996, holds at least 90 percent of its assets in qualified opportunity zone property and adheres other investment restrictions. Qualified opportunity zone property consists of tangible property purchased after 2017 that is brought into the zone for use or substantially improved within the zone. Substantial improvement is additional capital investment in tangible property equal to at least the initial cost of the tangible property and must occur within 2 ½ years.

Currently, opportunity zone funds are forming and receiving capital to deploy into communities that need it. So far, real estate is the predominant investment, though investors are hopeful upcoming Treasury regulation will encourage investment in privately operating businesses as well. An early list of funds can be found here.

The communities designated as opportunity zones are struggling. There is no one common story amongst the designated areas, but some themes arise. Many of these communities are rural or suburban areas that have been hit hard by globalization and outsourcing. Others are areas in once-vibrant cities that have seen their jobs replaced by automation and their population moving to easily accessible suburbs. The intention of the opportunity zone program is to incentivize investment in these communities by providing a tax subsidy.

The tax subsidy has three components:

Example

In 2014, an investor paid $600,000 for stock in a company and sold the stock for $1,000,000 in 2019, generating a $400,000 capital gain. Within 180 days of the sale, she reinvests the $400,000 capital gain into an opportunity zone fund, deferring the taxes owed. Her equity interest in the fund initially has a basis of $0 — as is the case with all opportunity zone funds — ensuring that when she eventually sells her equity interest, the deferred gain will be taxed.

In five years (2024), $40,000 (10 percent of the deferred capital gains) is added to the basis. By increasing the basis, $40,000 of the $400,000 deferred gain will not be taxed upon the sale of the equity interest in the opportunity zone fund.

At year seven (2026), another $20,000 (5 percent of the deferred capital gains) is added to the basis, further reducing the amount of the deferred gain that will be taxed. In 2026, the remaining $340,000 of the deferred gain will be taxed, and her basis in the fund will increase to $400,000. Keep in mind that this tax occurs whether or not the investment is actually sold in 2026.

If the investor chooses to remain in the fund for 10 years (2029), and her interest appreciates to $1,300,000, the tax on the incremental $900,000 capital gain is eliminated.

This program is new, and as such, there are many unanswered questions. The first set of proposed regulations, which were expected during the summer of 2018, were only issued in October 2018. Unfortunately, the recent federal shutdown disrupted the process for finalizing the regulations.

Critics have several concerns about the legislation, among them:

We share some of these concerns. This law is in its infancy, and the IRS will continue to clarify the details through regulations and rulings. We’ll know more over the next several months, and we’re sure there will be a Darden case on the program in the not so distant future.

The above article was prepared by Darden Professor Mary Margaret Frank and alumnus Ben Cullop (MBA ’11).

Opportunity Zones: 5 Things You Need to Know