Article

Article

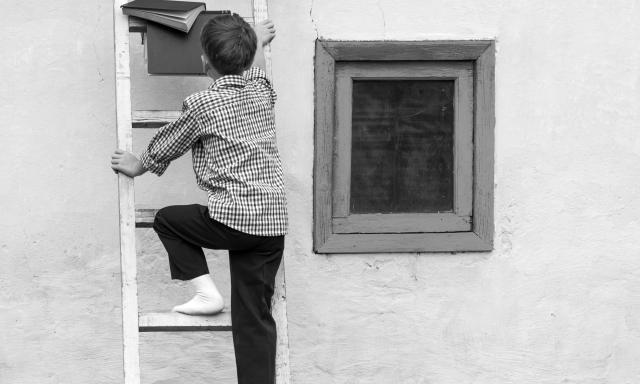

Growing up rich or poor has a tremendous impact on your life — studies show it affects health, prospects, confidence — what about the quality of your leadership? Darden Professor Sean Martin discusses the ripple effect that means childhood affluence may prove a liability in the workplace.

Growing up rich or poor has a tremendous impact on your life — studies show it affects health, prospects, confidence — what about the quality of your leadership? Darden Professor Sean Martin discusses the ripple effect that means childhood affluence may prove a liability in the workplace.

Insights from

Written by

We already know that growing up rich or poor has a tremendous impact on your life — but does it also affect how we treat others in the workplace? Whether or not we’re good leaders?

Yes, according to research done by Sean Martin, associate professor in leadership and organizational behavior at Darden, and his co-researchers.

Unlike studies that have tied growing up poor to disadvantages — worse health, limited job prospects, decreased longevity, and more — Martin suggests that growing up wealthy may work against effective leadership.

He found that growing up wealthy increased narcissism — which increased a leader’s confidence, but decreased their responsiveness to others. Martin and his co-researchers studied actively serving soldiers who were alumni of the United States Military Academy at West Point, using parental income data from admissions applications and surveying their followers to gain information on the graduates’ leadership styles.

“We saw a ripple effect. The more high income you were growing up, the more likely you were to be self-absorbed, and the less likely you were to be a person who listened to others, cultivated their trust and collaborated effectively,” Martin notes.

It’s an unfortunate paradox: growing up affluent increases the likelihood of a person getting to a leadership role in their career, but may be a liability once they’re in a position of power.

Childhood circumstances shape us profoundly, leaving a psychological “residue” Martin and colleagues observe. Kids who grow up in households that struggle for basic necessities (transport, child care, housing, meals) learn the value of relationships with others. Car broke down? Borrow a friend’s or accept a ride. Can’t afford day care? Ask a neighbor or relative to watch a child while working a second job. Rent increase? Move in with family to reduce expenses.

Children who grow up in lower-income households operate with a perspective that people need to rely on each other. They show greater sensitivity to others’ needs and care more about their reputations within groups. Some experiments show that people with lower-income backgrounds demonstrate greater generosity and empathy to strangers.

In contrast, in households where money is plentiful, children grow up feeling independent and self-reliant. Parents are able to provide for any goods or services needed; there are family cars to go wherever needed, at whatever time suits. They can hire tutors, sitters, coaches and plumbers. These families “perceive little need for others’ assistance,” Martin and colleagues write in an Academy of Management Journal article. Many buy into the “self-made” myth, in which they feel not only responsible for their own good fortune, but also entitled to having their voice heard above others.

Like other personality traits, narcissism exists on a spectrum. But studies show growing up wealthy increases self-regard and independence in ways that later affect workplace behavior. Leaders who are narcissistic tend to be self-confident and comfortable taking risks, traits that lead to initial success and popularity.

But the charm wears thin. Highly narcissistic leaders show less empathy, view themselves in grandiose terms, and are more likely to denigrate others and take credit for ideas that aren’t their own.

The weakness extends beyond relationships. From an operational standpoint, they’re less invested in task management and change-oriented work. Specifically, they’re less likely to structure tasks to meet long-term goals, less likely to conform to organizational rules and prone to impulsiveness. Touchy and defensive about feedback, narcissists are less likely to seek others’ input or be able to facilitate a genuine exchange of ideas within a group. In sum, they’re less effective both in daily operations and for longer-term strategic work, when thoughtful analysis and change is required.

In today’s flatter, more collaborative organizations, leaders need to be responsive to others, willing to question themselves, and able to formulate and pursue ethical business goals. As such, a narcissistic leadership style can be a significant disadvantage. Parental income is “often an unseen, unstudied and unaccounted for aspect of a leader,” but can lead to a sense of entitlement that is tough on the people who work for them, Martin and colleagues observe. Further, Martin writes, “Organizations might benefit from taking active steps to curtail the entitlement and grandiosity that at least some leaders with wealthy background are likely to exhibit.” Martin advocates that when hiring and promoting, companies should consider social class diversity — in addition to more “visible” forms of diversity such as gender and race — as a way to tap into different management strengths and styles.

Sean Martin co-authored “Echoes of Our Upbringing: How Growing Up Wealthy or Poor Relates to Narcissism, Leader Behavior and Leader Effectiveness,” which appeared in the Academy of Management Journal, with Stéphane Côté of the Rotman School of Management at the University of Toronto and Todd Woodruff of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point.

An expert in leadership, social class and ethics, Martin’s research addresses how organizational and societal contexts impart values and beliefs onto leaders and followers, and how those values influence their behaviors and experiences. His work has been featured in top academic journals, including Academy of Management Journal, Academy of Management Review, Journal of Business Ethics and Organizational Psychology Review, as well as mainstream media outlets including The New York Times, The Washington Post, Forbes, Fast Company, Inc., Harvard Business Review and Comedy Central.

Prior to joining the Darden faculty, Martin taught at Boston College’s Carroll School of Management and Cornell University’s Johnson Graduate School of Management.

B.A., University of California, Santa Barbara; MBA, California Polytechnic State University; Ph.D., Cornell University Samuel Curtis Johnson Graduate School of Management

Entitlement and Effectiveness: How Upbringing Affects Leaders

Share